Women’s Mentorship in the 1910s

Education for women was in flux in the first decades of the twentieth century. Female students and faculty still made up a small percentage of the university population at most universities and were largely relegated to domestic studies, such as Home Economics. Purdue University was no different. [1] However, there were significant women at this time stepping up to pave a new way for females in academia. This is the environment into which Emma Montgomery McRae entered and into which she poured her life and career. McRae was a professor of English literature at Purdue, beginning in 1887 and ending with her retirement in 1912. [2] She garnered the admiration and respect of peers and students alike, quickly coming to be known by both groups as “Mother McRae.” According to biographer and Purdue alumna Angie Klink, though McRae never officially received the title “dean of women,” she functioned in this role in every way, acting as “a counselor on every academic and personal problem these students experienced." [3] She involved herself deeply as a mentor and guide in the lives of many, and her students loved her immensely. The 1912 Debris yearbook, written by students, says that “the greatest influence among the girls is Mrs. McRae” and “it would be an impossibility to try to measure the account of good spread broadcast by our beloved teacher.” [4]

The following artifacts are just a small sample of the wide range of primary sources that testify to her involvement in the lives of young women and the legacy of that involvement. It is impossible to tell how far-reaching the impacts of her work were on the women (and men) of her day, but, if the award in her honor (Philalethean’s McRae Medal), [5] the club in her name (Muncie’s McRae Club), the life and career of her mentee Dean Carolyn Shoemaker, and the numerous accolades given to her over the years by peers and students alike are any indication, her presence and her voice were powerful. [6] Purdue saw significant advances for women during and just after her tenure. Women began branching out into fields previously unknown to them—1919 saw Purdue’s first female graduate of the College of Agriculture [7]—and the role of Dean of Women was formalized directly after her retirement with Dean Shoemaker. [8] If, as Klink suggests, “with Emma, the die was cast,” [9] McRae's groundbreaking work may very well have been a significant part of such advances.

Concerning the Education of Girls: A Paper

Alongside her work in the field of literature, McRae also dedicated herself to exploring multiple facets of pedagogy in order to advocate for students. This is what allowed her to become the first female president of the State Teachers Association in Indiana. [10] Engaging in the discussion of pedagogy at the university level, she published “Concerning the Education of Girls: a Paper” during her career at Purdue. [11] Pictured here is the cover of the paper, which is sixteen pages total. Though the cover indicates that the paper was “Published by the University,” [12] that is the only available information that establishes the context surrounding the paper. While we can assume it was written during her Purdue tenure (1887-1912), we have no date of publication and no information on whether she presented the paper or for whom it was written or presented. It quickly becomes clear from the content of the essay, though, that, whoever her audience is, she is attempting to persuade them to accept and embrace the changing nature of women in higher education and in the workforce.

In the paper, she makes an impassioned case for how education must prepare women so that they “may best perform the duties that come to [them].” [13] However, she reframes these duties from the traditional notion of "female duties" into a far broader one. She boldly asks, “who can determine the station of the American girl?” and asserts that “[t]he possibilities for her usefulness seem limitless.” [14] Where, traditionally, women were encouraged to learn just enough to fulfill the domestic role of wife and mother, McRae reaches beyond this, stating: “she should be given the opportunity to become well grounded in the essentials of such education as shall fit her to grace the home that father and husband may make for her, to make a home or continue one for herself if taste or circumstances compel it, and also to lend a hand in making other homes holier and happier.” [15] In a move innovative for the turn of the 20th century, when most women were actively barred from participation in courses deemed “unwomanly,” [16] she satisfies the traditional, conservative notion of female “duty” but also maneuvers it into a global duty, where women are encouraged to take charge not just in the domestic sphere of the physical household and family but in the broader and recontextualized “homes” they may make for themselves. In other words, McRae subtly attempts to break down the barriers female students were facing in taking courses and, later, entering jobs. She discusses numerous possibilities for how this practically changes female education, from encouraging women to learn “sanitary science” in order to improve and preserve life in domestic spaces to advocating for women to be allowed to enter the almost entirely male-dominated industrial/factory arena to receive “industrial training” so that they may “compete with their brothers in the realm of ideas.” [17]. She poetically ends the piece with a rally cry for women, where she insists that “[t]he girl of today must help to turn the sighs of struggling humanity into songs of rejoicing for the dawning of a better day." [18]

Philalethean Literary Society Constitution -- McRae Medal

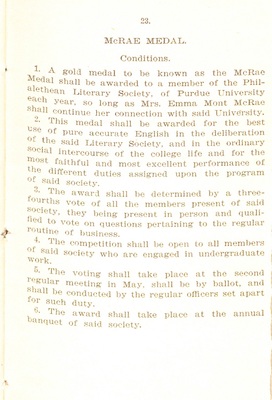

In this amendment to the original constitution of the all-female organization the Philalethean Literary Society, the influence of McRae’s mentorship is evidenced through an annual award presented in her honor to one of the women of the society. [19] The award was to be presented for “pure accurate English in the deliberation of the said Literary Society, and in the ordinary social intercourse of the college life and for the most faithful and most excellent performance of the different duties assigned upon the program of the society." [20] While the text of the award does not specify much further, it seems this award celebrates several of the qualities lauded in McRae herself: her character, her interpersonal influence, and the quality of her scholarship. McRae was known around Purdue as one who “epitomized high character, delivered masterful speeches, and garnered immense respect.” [21] When it came to her relationship with the female students with whom she worked, she “served as a counselor on every academic and personal problem these students faced” [22] and was even listed as an honorary member of Philalethean in the 1910s. [23]

McRae was a persistent advocate for women’s scholarship, a compassionate and encouraging mentor, and an inspiring, unwavering presence in university life. [24] This award celebrates these qualities and encourages the next generation to carry them on through their work in Philalethean, at Purdue, and in the workforce.

1913 Debris Emma Montgomery McRae Retirement Commemorative Page

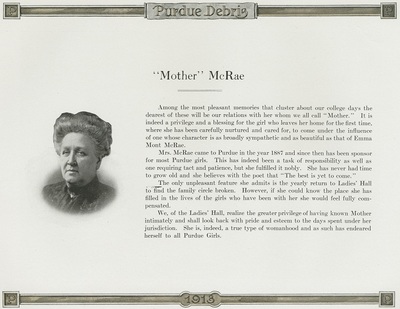

Following her retirement in 1912, the 1913 Purdue Debris yearbook includes this tribute to McRae in its Co-Ed (i.e., women’s) section. [25] She is dubbed by her students “a true type of womanhood” who “has endeared herself to all Purdue Girls.” [26] The writer of the piece describes the experience of the women as they encounter McRae: “It is indeed a privilege and a blessing for the girl who leaves her home for the first time, where she has been carefully nurtured and cared for, to come under the influence of one whose character is as broadly sympathetic and as beautiful as that of Emma Mont McRae.” [27] As these words imply, “Mother” McRae came to step in as a mother figure for her students and gave these women a space to experience belonging. She made them family in a world where, because of the male majority, they were excluded from much. Female faculty, like McRae and, later, those officially filling the role of Dean of Women, became male leadership’s viable solution to “insulate the women from the ‘maleness’ of the campus” and deal with “‘unpleasant’ female needs." [28] However, many of these women, McRae included, took up a greater mantle and created tight-knit, empowered communities of well-supported female scholars. As Angie Klink describes: “[t]hey would…protect and guide the women” and “were scholars who were concerned about the intellectual development of women, especially in competition with men.” [29] In both her community-building and her advocacy for her students, McRae carved out a home, a place where the ever-increasing female minority not only felt welcomed but also were encouraged to rise up to meet their full potential in higher education This piece evidences the legacy she left through the environment she created, which allowed women to begin to flourish at Purdue and beyond.

Author Bio:

Elise Robbins is a first-year Master of Arts student in the Literature, Theory, and Culture program at Purdue University. She graduated with her BA in English literature and linguistics from Purdue University in 2014. Her research interests include early modern religious writing in its cultural and material contexts as well as the application of translation theory to the translation of religious texts.

[1] Angie Klink and Natalie Powell, The Dean's Bible: Five Purdue Women and Their Quest for Equality (West Lafayette: Purdue University Press, 2014), 5.

[2] Klink and Powell, 5-7.

[3] Klink and Powell, 5.

[4] Purdue University, Debris 1912 Yearbook (PUD00025, West Lafayette, IN: Graduating Class of 1912, Purdue University Archives and Special Collections, West Lafayette, 1912, Accessed on April 8, 2019, http://earchives.lib.purdue.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/debris/id/29682/rec/25), 186.

[5] Philalethean Literary Society, “McRae Medal,” (circa 1890-1910. Box 1, Folder 1, Item 2, page 23, Philalethean Literary Society Records, Purdue University Archives and Special Collections, Purdue University Libraries).

[6] Klink and Powell, 4-5.

[7] David M. Hovde, Adriana Harmeyer, Neal Harmeyer, and Sammie L. Morris, Purdue at 150: A Visual History of Student Life, (West Lafayette: Purdue University Press, 2019), 6.

[8] Klink and Powell, 3.

[9] Klink and Powell, 5.

[10] Klink and Powell, 4

[11] McRae, Emma Montgomery. “Concerning the Education of Girls: a paper,” (circa 1890-1910, Box 1, Folder 2, Item 1, Montgomery McRae papers, Purdue University Archives and Special Collections, Purdue University Libraries).

[12] McRae, 1.

[13] McRae, 4.

[14] McRae, 4.

[15] McRae, 4-5

[16] Klink and Powell, 5.

[17] McRae, 5-6; 12.

[18] McRae, 15.

[19] Philalethean Literary Society, “McRae Medal.”

[20] Philalethean Literary Society, “McRae Medal.”

[21] Klink and Powell, 5.

[22] Klink and Powell, 5.

[23] Philalethean Literary Society, Event Program, (1913. Box 1, Folder 6, Item 1, Philalethean Literary Society Records, Purdue University Archives and Special Collections, Purdue University Libraries).

[24] Klink and Powell, 5.

[25] Purdue University, Debris 1913 Yearbook (PUD00026, West Lafayette, IN: Graduating Class of 1913, Purdue University Archives and Special Collections, West Lafayette, 1913, Accessed on April 8, 2019, http://earchives.lib.purdue.edu/cdm/compoundobject/ collection/debris/ id/26506/rec/26), 185.

[26] Purdue University, Debris 1913 Yearbook, 185.

[27] Purdue University, Debris 1913 Yearbook, 185.

[28] Klink and Powell, 8.

[29] Klink and Powell, 8.