Voices, Identities, & Silences: Investigating 150 Years of Diversity in the Purdue Archives

Welcome! This online exhibit features artifacts from the Purdue University Libraries’ Archives and Special Collections, which houses and preserves the material history of life at Purdue. The central theme of this exhibit is “diversity,” a term that most will recognize as signifying the range of identities that fall outside what is “normal” or “average.” And such identities will certainly be represented here—women, African-Americans, the LGTBQ+ community, and people from elsewhere in the world are all featured in these artifacts. But more than that, we hope visitors to this exhibit recognize that the diversity documented here is a product of Purdue University as a time and place within which many different sorts of people work to create a shared world. While Purdue may be most frequently associated with its engineering programs, its men’s varsity basketball team, or its agricultural research, Purdue’s past, present, and future is made up of much more than these. And not all of this history is (or will be) preserved in the university’s archive. Inevitably, some people and events are judged to be more important and thus more worthy of preservation. Our exhibit, then, aims to focus attention on elements of Purdue’s history that have been otherwise overlooked, not in order to “correct” that history but rather to expand it and (if our aim is true) change our understanding of what “counts” as that history in the first place.

In his work on the relations between historical documentation and political power, historian Michel-Rolph Trouillot argues that the acceptable narratives of what happened in the past emerge through the creation and maintenance of distinctions between fact and fiction. [1] This includes, he suggests, the standard procedures for recording, preserving, and explaining evidence. [2] According to this line of thinking, making a sustained historical inquiry often means identifying the silences that structure the currently accepted version of that history. [3] By opening up and looking into the stories and artifacts that were left aside in order to create the dominant narrative, researchers can help to transform that narrative into something that more accurately reflects the world that formed that prior moment in time and space.

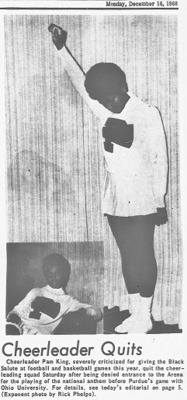

As you move through the exhibit, you may notice (if you proceed chronologically) that the forms of diversity represented by each page become more and more varied as you go along. Whereas three out of the first four pages focus on women’s history at Purdue, the later decades feature a broader range of issues and identities. This reflects the dominant tendency of Purdue’s (and indeed America’s) approach to diversifying exclusive spaces: first, it takes a while for gender segregation to erode, and then other forms of exclusion recreate this erosion more quickly and with varying degrees of success. You may also notice that some of the history shown here reflects a strategy of change-from-within-the-system, while other artifacts reflect a willingness to engage in bolder and more confrontational forms of protest and advocacy. While each individual visitor may experience strong identification toward one or the other side of this dynamic, we encourage you to consider closely how each of the stories shown here reflects both individual assertions of agency and also broader sociopolitical pressures. And, above all, we hope you find yourself rethinking your own answer to the question “Who is Purdue?”

From Our Exhibit:

[1] Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Boston: Beacon Press, 1995), 6-10. Trouillot explains: “The need for a different kind of credibility sets the historical narrative apart from fiction. This need is both contingent and necessary. It is contingent inasmuch as some narratives go back and forth over the line between fiction and history, while others occupy an undefined position that seems to deny the very existence of a line. It is necessary inasmuch as, at some point, historically specific groups of humans must decide if a particular narrative belongs to history or to fiction. In other words, the epistemological break between history and fiction is always expressed concretely through the historically situated evaluation of specific narratives” (8).

[2] Trouillot frames this as “historical production”: “[H]istory reveals itself only through the production of specific narratives. What matters most are the process and conditions of production of such narratives” (25).

[3] Trouillot, 26-30. He in fact suggests that there is a necessary relation between “facts” and “silences” which must be taken into account within historical research: “[F]acts are not created equal: the production of traces is always also the creation of silences. Some occurrences are noted from the start; others are not. Some are engraved in individual or collective bodies; others are not. Some leave physical markers; others do not. What happened leaves traces, some of which are quite concrete—buildings, dead bodies, censuses, monuments, diaries, political boundaries—that limit the range and significance of any historical narrative” (29).