Civil Rights Protests in the 1960s

Relations between the administration and the student body had gotten off to a rocky start in the 1968-9 school year, when the editor-in-chief of The Purdue Exponent, William R. Smoot II, gave a speech at freshman orientation that the administration considered obscene. [1] For the remainder of that year, the conservative leanings of the administration clashed with the increasingly-progressive student body, and the Exponent reported on the multiplying conflicts with a mix of righteous anger over the injustice involved and a somewhat gleeful spirit of provocation. By the end of the school year, the Hovde administration would have escalated to setting the local police on peaceful student protestors, resulting in over 200 arrests. [2] This is all by way of providing context for the particular event this exhibit will focus on, which occurred near the end of the fall semester of 1968. The reader may recognize this sequence of events as being fairly relevant to current issues and arguments.

It was November, 1968. One month before, Tommie Smith and John Carlos had performed the famous raised-fist “Black Power” salute at the Olympic games. At the Purdue Homecoming game, two cheerleaders decided to follow Smith and Carlos’s example. The following description of the event appeared in the November 20 issue of the Exponent:

It is likely that the attention of most of the crowd was focused on either the spectacle on the field, the ocean of people on the stands, or the “clear October sky” above. But some may have glanced towards the sidelines and seen two black cheerleaders standing with fists in the air and heads bowed. [3]

The cheerleaders in question were Pam Ford and Pam King. Unlike Smith and Carlos, they did not wear black gloves for the salute — they instead raised a black pom-pom. [4] The Exponent published a full-page “feature” in open support of Ford and King, accompanied by testimony from other black students about the prevalence of racism on the Purdue campus and the cultural significance of what was then called the “Black Salute.”

As the reader proceeds through the following artifacts from the period and takes in the community reaction to this event, I would encourage them to consider how closely it hews to the controversy that erupted over Colin Kaepernick “taking a knee” fifty years later. [5] Note also that some of the aforementioned racism is pretty blatant, both in terms of the administrative reaction to Pam King and in the text of some anonymous letters written to the Exponent.

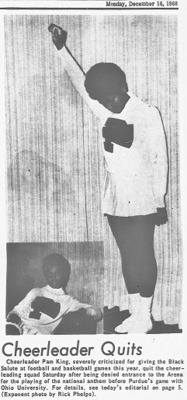

Photograph of Pam King, Dec. 16.

Ford and King performed the Salute a second time during the next game; at this point, presumably people realized it wasn’t a one-off event, and evidence of the anti-Salute camp started appearing in the “Letters” section of The Purdue Exponent. [6] Over the next few issues, the Exponent ran a fairly problematic but well-intentioned editorial on the salute as a “symbol of hope,” [7] and a steady stream of articles about institutional racism. Ford, at this point, disappears from the narrative for her own reasons — possibly because pressure was being applied by the faculty, administration, and other cheerleaders — but King gave the Salute a third time, at a basketball game, and official action was taken.

The cheerleaders, their faculty advisor, and the Athletic Director had some behind-the-scenes discussions that, by their nature, are not well-documented. While the actual discussions are not on the record, the decision that they arrived at as a result of said discussions was made public: an agreement that the cheerleaders needed to come up with an official code of ethics for their organization, and until it was decided whether the Black Salute was permissible, they would not appear during the National Anthem at all. An article published in the Exponent after the matter came to a head included this explanation of how things stood at that point:

Athletic Director Guy “Red” Mackey, who has been more than a little red-faced over quite a few activities which he terms “radical” on campus these days, says the salute is personally offensive to him regardless of Pam’s open admission that the gesture is her race’s personal means of showing reverence to the flag and unity among the disenfranchised black people. Mackey, however, agreed to let the cheerleaders make their own decision as to whether they would go on the floor for the national anthem and whether they would let Pam do the salute. When he admitted this to black cheerleaders Pam Ford and Mrs. King last Friday, they asked him what would happen if the cheerleaders came to a positive decision concerning the salute and he said “I can’t prejudge myself.” [8]

As it turns out, a decision had in fact been made. When the cheerleaders decided to come back out during the Anthem on December 14, they found that campus security had standing orders from the Athletic Department to bar the cheerleaders entry. It was this incident that led King to resign in protest, and this photo ran on the front page of the next issue of the Exponent.

Letters to the Editor, Dec. 4-18

Note that there are several letters here -- by clicking on the one visible, you can see the others.

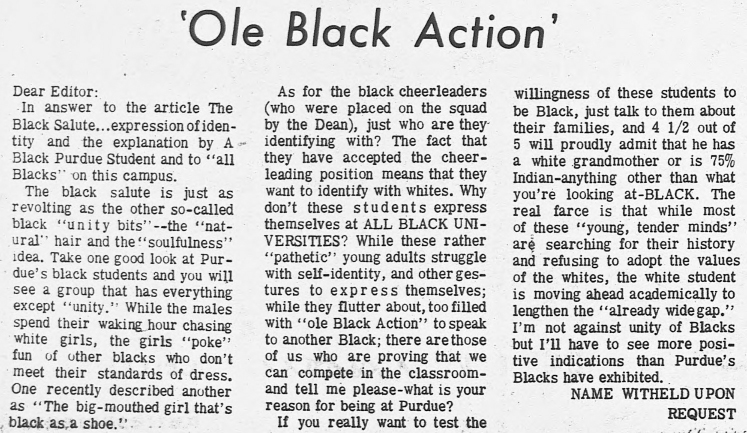

After the second time King and Ford performed the Black Salute at a Purdue game, members of the community began voicing their opinions on the action in The Purdue Exponent. The letters reproduced here range from a few days after the aforementioned second game up until Pam King’s detailed interview was printed two weeks later. These letters display the range of opinions within the community, and the passion with which these opinions were expressed.

The first letter printed, entitled “Ole Black Action,” is both anonymous and appallingly racist. [9] Note that not only does the writer refer to the Salute and other aspects of African-American culture as “revolting,” but they bring in the old racist fear of black men “chasing white girls.” They also make it clear that they think African-American students do not belong at Purdue University at all, much less on the cheerleading squad.

David Pogue’s letter, “Clenched Fist Accepts No Friendship” appears on a later page of the same issue. It is less openly racist, but the reader may recognize in it an eerily familiar form of covert oppression practiced through the present day — Pogue [10] expresses his ostensible concern that this method of protest is unnecessarily disrespectful or disruptive, and makes obtuse reference to “legitimate protests.”

At the basketball game against North Dakota on December 5, Pam King performed the Salute alone. The following Monday, another anonymous letter appeared in the Exponent, even more virulently racist. Letters in response to the anonymous racist followed, from Becke Herrin, [11] Eric Williamson, [12] and Ken Rhodes. [13] Rhodes’s letter ends with a particularly striking statement that gives us insight into what isn’t being printed, preserved, or publicized: “I had to write because his letter was ‘so, Purdue.’” This reminds us that we can’t fully judge the climate of Purdue in decades past from official publications — while very few preserved documents from fifty years ago display the open racial hatred of this anonymous letter, such sentiments were apparently not uncommon. Rhodes read this unhinged, racist screed and felt that it was typical of his experience of the Purdue population; that he had to write in criticizing it not because it was the work of a fringe lunatic, but because it represented a pervasive opinion among the community.

It was that Saturday that, as mentioned previously, the cheerleaders were barred from entering during the national anthem. Tuesday’s Exponent contained the extremely short “Open Letter to the Athletic Dept” from Roger Millen, [14] which is interesting mostly in how context-dependent it is, consisting as it does of a single sentence fragment. The next day, Paul Conway’s letter appeared, in which he sarcastically excoriates the “super patriots” who are trying to suppress self-expression that they find threatening, such as the Black Salute. It is unclear whether Conway [15] is referring solely to elements in the Purdue administration — such as Athletic Director Mackey — or to other students and faculty who are likewise offended by King’s gesture. Conway’s letter was the last to appear on the subject, as in the following issue of the Exponent, an in-depth interview with Pam King herself was published. It is unclear whether the cessation of letters is because the interview calmed the right-wing outrage, because the Exponent staff felt that King’s interview was the final word on the matter, or because this took place during the last week before winter break, and those offended forgot about it before the next semester started.

Interview with Pam King After Her Resignation, Dec. 19

The week after she resigned from the cheerleading squad, Pam King gave an interview to the Exponent. The resulting article, by Stephanie Salter, is a platform from which King expresses herself and her views eloquently. It largely speaks for itself, but here are a few key quotes from King:

The fact that the university seems to say yes, black students can do the Black Salute but they cannot do it in a university uniform, seems to say black students can be black, but not representing Purdue. There are black students at this campus and blackness must be a part of Purdue University. The purpose [of the action] was to keep black cheerleaders from doing the Black Salute where thousands could see. How will thousands come to the conclusion that black man has the right to do the Black Salute when the Salute is banned from that public?

We can see from the beginning that King has a shrewd grasp of the rhetorical context; her analysis that the administration wants to “say black students can be black, but not [while] representing Purdue” is spot on. She also expertly highlights the problematic implications of any attempt to ban public performance of the Salute. King went on to connect her experiences to the social movement of her time:

I can understand the frustration of blacks like Stokely Carmichael, H. Rapp Brown and Malcom [sic][16] X who refuse to talk and to explain to whites. In the final analysis — prejudice and discrimination will overrule the explanation and pleading of the black man. I resigned from the cheerleading squad because it was overpowered by discrimination and prejudice. As long as I did as the whites dictated, my presence was accepted. The minute they were asked to respect my feelings as a black person, if they couldn’t understand them, I became intolerable. Such will be the plight of any black person who veers from the white standards of tolerable.

One of the notable comments in this particular quotation is that King suggests at least some of the other cheerleaders were opposed to her performance of the Salute. The internal debate among the members of the cheerleading squad is not made public or explicit, but this is one of several comments that indicates those debates were fairly heated, and that King came away with a (likely justified) grudge against some of her fellow cheerleaders. She also notes that, in a meeting between the cheerleading squad, the pep committee, and the pep band, someone put forth the idea of expelling her from the squad — “The charges were a personal dislike for the Black Salute,” King said — but was voted down.

Other important lines from King’s interview include her characterization of the administrative approach to the Black Salute controversy: “No one from the Athletic Department has ever approached me about the Salute. Everything has been done as if we were children to be dealt with by our superiors.” It is also likely instructive to read her thoughts about being on the cheerleading squad as a black woman — which was apparently a fairly new experience for Purdue:

I knew no matter what happened I wouldn't give up any blackness for it. The squad didn't want us last year, but the motivating factor in their acceptance was the feared reaction of the black football players. The cheerleading squad maintains they accepted the blacks to expose the blacks to the public. But when blackness appeared, they attempted to suppress it.

King goes on to say that the white cheerleaders acted as if “they had done the blacks a favor” by allowing them onto the cheerleading squad, and that they therefore felt as if King and Ford “owed” them and should be willing to cease performing the Salute. The article concludes with King explaining the symbolism behind the Salute and calling for the progressive elements of the community to be just as vocal as those who want to suppress the Salute.

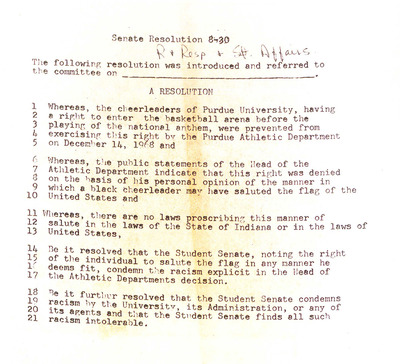

Student Senate Resolution, Undated

The controversy over King’s performance of the Salute did not, however, die down completely over the break. In the coming semester, King would demand that the university officially censure the administrators, faculty, and students involved in the discrimination shown to her — though there are no explicit records of this surviving, it is heavily implied in the letter she sent demanding said censure (not included in this exhibit for reasons of space) [17] that, in addition to Athletic Director Mackey barring her entry to the game on December 14, she faced significant pressure and ill-treatment from other cheerleaders and possibly the faculty advisor of the cheerleading squad. Though some members of the squad supported her, and accompanied her on the 14th, it is clear from reading between the lines that the others did not. For instance, we know the cheerleaders missed two games before the 14th because they could not come to an agreement — thus implying a significant divide in among the squad. Also, in the aforementioned letter, King was not shy about asking for the cheerleading organization in general to face official censure; this indicates that she faced opposition from the rest of the squad, not just the administration. Also, another member of the cheerleading organization admitted, in an article that ran in the Exponent on Dec. 17:

Socially, everything went fine on the squad all this fall and I suppose some may have construed this as racial harmony. But when the very first racial issue came up — on the very first racial confrontation — there was a problem and as usual, white supremacy won out in the final analysis. [18]

Thus, in the spring semester of 1969, official bureaucratic machinery was grinding to life.

I think it is instructive to compare and contrast this document, from the student senate, with the next document, from the university senate. The student senate is unapologetic in its support of King and its condemnation of Mackey, and goes so far as to call Mackey’s decision out for its “explicit” and “intolerable” racism.

University Senate Minutes, Jan.-Feb. 1969

The attempt by the university senate to address this issue stretched over two sessions and caused much consternation. In the minutes for the meeting in January (the first page is the photograph on the left; the other pages can be accessed by clicking on said photograph), the committee tasked to deal with this matter provided a sizable document on the subject and a clipping from the Lafayette Journal & Courier [19] wherein King gives her view of what the Salute means. According to the agenda of this January meeting, unspecified “discussion” occurred.

In the next meeting of the university senate, on February 17, the following unfolded. First, King addressed the senate personally; what she said is not recorded. Discussion is opened on the proposal that they adopt the following statement:

The University should assume no official position, either of approval or of disapproval, on expressions of special significance to individuals, such as the Black Salute. In particular, such expressions in themselves do not furnish sufficient grounds for direct or indirect disciplinary action by University students, faculty, staff, or administrative offices.

A recommendation from the student senate is discussed, which supports the above but also asks that the senate more directly address the actions of the Athletics Department and make it clear that the action of barring King from entry qualified as “indirect disciplinary action.” Discussion follows. Professor Albert Kahn [20] changes “disciplinary action” to “preventative or disciplinary action,” thus covering Mackey’s actions on the 14th but not openly calling him out.

Professor Jack Long [21] attempted to remove the sentence about disciplinary action entirely and replace it with the following, which is more or less an endorsement of Athletic Director Mackey’s actions:

Any group of students, such as the Cheerleader Team, participating in any activity where they represent the University, their conduct and methods of presentation be determined in consultation with their faculty advisor(s), prior to the performance, to the mutual satisfaction of the student group and their faculty advisor(s).

The amendment was “discussed at length” and defeated by a very narrow margin. [22] Professor Paul Simms [23] then attempted to add a new sentence to the end of the document, as follows:

Any individual who is participating in an official activity of the University should act in such a manner as to clearly show his respect for the National Anthem, the Flag, and the Republic for which it stands.

The ways in which this addition is problematic and entirely counter to the unamended document should be clear to the reader without further explanation. Simms’s motion was defeated by a more sizable margin, [24] but I would still say far too many people were comfortable voting for it.

The document was tabled, and brought back for a vote in the following form, rewritten by Professor James W. Cobble [25]:

The University should assume no official position on the Black Salute. In particular, this expression does not furnish sufficient grounds for direct or indirect preventive or disciplinary action by University students, faculty, staff, or administrative officers.

This version was “carried by voice vote” with no discussion mentioned. While it seems largely identical to the original, there’s one very interesting change that I think indicates why there was so much discussion previously, but no discussion on this version. A large chunk has been excised from the first sentence, which you may recall originally read (deleted material in bold):

The University should assume no official position, either of approval or of disapproval, on expressions of special significance to individuals, such as the Black Salute.

It’s that second deleted portion that I think was the dealbreaker previously. The difference between its presence and absence has a significant rhetorical and semantic effect on the motion. Previously, this was a broader statement that could have set a precedent protecting student expression in general; the revised version addresses only the Black Salute. Here we can come back to the comparison with more recent events — under the original version, other forms of peaceful, silent protest (such as “taking a knee”) at a university event would have been protected speech, and students engaging in them would not be subject to punishment. The revised version, without the language bolded above, would allow the university to punish students who “took a knee”, raised a peace sign, or any other such gesture at future Purdue games.

The Purdue Exponent noted the change — an article on the resolution as passed explained that the original “had been questioned earlier because a number of senators said that the original document would allow students ‘representing the university’ to do anything they pleased in relation to individual expressions,” and that “The Cobble amendment restricted the proposed University Senate action to a statement on the Black Salute and on no other personal expression.” [26]

Author Bio:

E. C. McGregor Boyle III is a second-year PhD student in English Language & Linguistics at Purdue University.

[1] For the curious, it was about personal freedom after having left home, and he made more reference to sexual freedoms than the conservative elements of the administration liked.

[2] William R. Smoot II, “Reviewing the Revolution”, Bauls 2, no. 1 (1969): 11, Box 2, Folder 5, Collection of Student Newspapers at Purdue University, Purdue University Archives and Special Collections, Purdue University Libraries.

[3] Sharron Saveland, “The Black Salute… Expression of Identity”, Exponent 84, no. 51 (1968): 3. https://exponent.lib.purdue.edu/?a=d&d=PE19681120-01.1.3

[4] The photograph we have of this shows King performing the salute without the pom-pom, but other descriptions of the multiple incidents in which she performed it describe her and/or Ford using it in place of a gloved fist. Presumably, Purdue cheerleaders at the time carried one pom-pom in each of the school’s colors, facilitating this gesture.

[5] If anyone is unfamiliar with the controversy over Colin Kaepernick, the summary is as follows: in 2016, Kaepernick began to opt out of standing during the anthem as a protest against racial injustice. Many other players followed his lead. Many conservative elements were outraged by this form of silent protest, and a controversy followed that has an awful lot in common with Pam King’s experience as explored below.

[6] You can find these letters elsewhere in the exhibit.

[7] “Symbol of Hope”, Exponent 84, no. 57 (1968): 8. https://exponent.lib.purdue.edu/?a=d&d=PE19681205-01.1.8

[8] Kent Hannon, “How Right is White?”, Exponent 84, no. 65 (1968): 8. https://exponent.lib.purdue.edu/?a=d&d=PE19681217-01.1.8

[9] I personally suspect the Exponent only published this letter, and the other anonymous item mentioned later in this document, out of mischief. At the time, the Exponent was regularly criticized (somewhat unfairly) for not giving the conservative segment of the university a sufficient voice; it seems in character for then-editor William Smoot to respond to this in a passive-aggressive manner by printing some of the more disturbing right-wing letters he received, thus giving the conservative students a voice while simultaneously letting them discredit themselves.

[10] Pogue is, of course, speaking from a position of white privilege — I double-checked to make sure he was, in fact, Caucasian, and found a picture of him on p. 496 of that year’s Debris.

[11] Herrin, despite being a member of the apparently-all-white sorority Pi Beta Phi (see p.361 of the 1968 Debris), is passionate in her support of Pam King and the ideals that the Salute represents.

[12] Williamson’s letter was the first from an African-American on this controversy, though the Exponent’s original article on the homecoming game did include African-American voices in their discussion of Ford and King’s actions.

[13] I am unable to find any information about Mr. Rhodes, which is unfortunate, because his letter is very interesting.

[14] If this is the same Roger Millen who appears again in the Exponent on February 18, 1969, we know that he is an instructor in Industrial Engineering, a PhD candidate, and a former lieutenant in the U.S. Army.

[15] The identity of Paul Conway, like that of Rhodes, eludes me.

[16] This is apparently a spelling error on the part of the Exponent, not King, since the article indicates that she gave a verbal interview, not a written statement.

[17] The letter, specifically, was sent to the Dean of Men and the Dean of Women, and consisted of an official complaint asking for the Purdue University Cheerleading Squad to lose their “status as a recognized organization” because of their “discrimination on the basis of race”. The letter wasn’t published at any point, though the fact that an official complaint was lodged was mentioned in Exponent articles in the spring semester of 1969, while the University Senate was still debating their response (as discussed below). We have a copy now because Dr. Barbara Cook — who was at that time part of the Dean of Women’s staff, but who would become Dean of Students in 1980 — made a practice of collecting documentary evidence of the student/administration conflicts of the late 1960s, and her binders of this material were included in her papers when they were donated to Purdue. This copy of the Student Senate resolution also comes from Dr. Cook’s binders.

[18] Kent Hannon, “How Right is White?”, Exponent 84, no. 65 (1968): 8. https://exponent.lib.purdue.edu/?a=d&d=PE19681217-01.1.8

[19] Or, as this esteemed document actually reads, the “Jounral and Courier”.

[20] From the Department of Biological Sciences.

[21] Animal Sciences.

[22] 37-34.

[23] Physics.

[24] 43-24.

[25] Chemistry.

[26] Wray, Ron. “Senate Passes Resolution”. Exponent 84, no. 80 (1969): 1, 7. https://exponent.lib.purdue.edu/?a=d&d=PE19690218-01.1.1