Alcohol and Prohibition in the 1930s

Alcohol tends to be a subject of controversy on college campuses, but during the first few decades of the twentieth century it was a serious political issue, at both the local and the national level. The temperance movement, which started back in the nineteenth century, framed alcoholic substances as a drain on America’s productive activity and a morally corrupting force among the nation’s people, especially working families. By the 1930s, then, the temperance movement had actually been wildly successful in political terms—in 1919, the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution made alcohol totally illegal, and the subsequent Volstead Act gave the federal government legal authority to enforce it in 1920—but in cultural terms, a large portion of the country felt otherwise. While much of America in the years leading up to prohibition had been rural and religious, after the laws were in place there was a period of accelerated urbanization and modernization that made for a stark juxtaposition between the culture that promoted prohibition and the culture that resisted it.

Because Purdue served as a modernizing force for a relatively rural population (in fact, Indiana passed its own prohibition laws in 1917, two years before the federal government did), the campus community had its share of dissent and debate with regard to alcohol. Some students actively supported and agitated for the prohibition amendment and its enforcement, for reasons that ranged from progressive political beliefs to evangelical Christian fervor. Other students drank anyway, since the emerging national culture based in commerce and media gave no reasons why they shouldn’t, given that alcohol was often available despite the law. By the time the 18th Amendment was repealed at the end of 1933, public favor had drastically turned away from the prohibition movement, though even then not every American supported alcohol. In fact, Purdue remained a dry campus for many years after that, as it had been even through all the debate and resistance during the prohibition years.

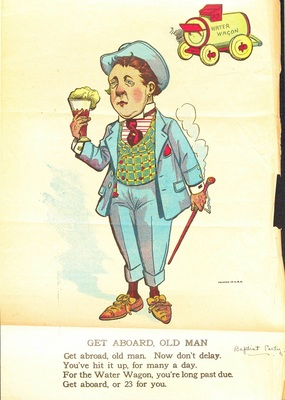

Temperance Movement Water Wagon Cartoon

This paper flyer comes from the scrapbook of Opal D. Stech, a Purdue student during the years 1928-1932. The flyer features a color-printed cartoon image of a man with red cheeks and sagging eyes, holding a foaming-over glass of beer and smoking a cigarette. Behind his right shoulder is a water wagon, labelled as such and bearing the number 23. Below the man is a bit of verse:

GET ABOARD, OLD MAN

Get abroad (sic), old man. Now don’t delay.

You’ve hit it up, for many a day.

For the Water Wagon, you’re long past due.

Get aboard, or 23 for you.

The image of the “water wagon” as a symbol of sobriety remains in the American vernacular term “fell off the wagon,” referring to a relapse into addiction or alcoholism. “23” (or “23 skidoo”) is an antiquated slang term meaning “over” or “gone,” so the “23 for you” phrase in this context means roughly “it’s over for you.” A small piece of marginal handwriting to the right of the verse reads “Baptist Party.”

Elsewhere in the scrapbook there are documents pertaining to Stech’s membership in the evangelical community of Lafayette’s First Christian Church: Sunday service programs, announcements of speeches by traveling preachers from the “Evangelistic Party,” and, notably, the church’s 1931 “Youth Day” program. The 1931 program lists Stech as representing senior students from Purdue, and it also includes an announcement for a Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) convention to be held the following month. (The WCTU were a very prominent prohibition and temperance organization.) The announcement includes a short paragraph meant to rally the (continuing) prohibition cause: “The ‘wets’ are saying, ‘the return of intoxicants would restore prosperity.’ The (sic) why are Germany and England, the heaviest drinkers in the world, on the verge of bankruptcy—holding out the tin cup for hand-me-outs from rich Uncle Sam—the dry uncle? It is not an accident that the richest and happiest nation in the world is the driest nation in the world.” [1]

Since the “Get Aboard, Old Man” flyer has no context or attribution other than the handwritten “Baptist Party” (perhaps referring to the Evangelistic Party?), we can posit either that Stech may have attended some part of the WCTU convention or that one of the evangelist speakers noted in her scrapbook also vouched for prohibition and temperance. Those are only speculative possibilities, however; in any case, we can assume that Stech felt some degree of conviction toward prohibition as a movement, and that this was in relation to her faith as an evangelical Christian.

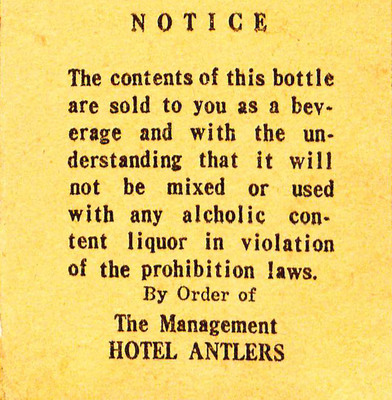

Prohibition Notice from the Antlers Hotel

This note is from the scrapbook of Wilbur A. Schmitt, a Purdue student during the years 1924-1928. It has been placed among several pages of invitations to fraternity and sorority dances and social events. Included nearby, on the same page of the scrapbook, is an invitation to the Phi Kappa Rho Annual Dinner and Dance on Friday, February 20, 1931, located at the Antlers Hotel. Schmitt is listed on the “Membership” page of the invitation, which is printed on card stock and bound with string into a booklet with purple cardboard covers and several pages of information about the event. Above the note pictured here, there is a round hole in the card, which appears to be there so that the note can be placed around the neck of a bottle. Presumably, this note came attached to a soft drink that Schmitt received before or during this dance, reminding him that it should not be mixed with alcohol. It reads: “NOTICE: The contents of this bottle are sold to you as a beverage and with the understanding that it will not be mixed or used with any alcoholic content liquor in violation of the prohibition laws / By Order of the Management / HOTEL ANTLERS.” [2]

Such a note would presumably hold less value than the other memorabilia in these pages, since the invitations and dance cards would have been used specifically to participate in the events memorialized. Perhaps Schmitt thought the note was funny because it was presumptuous and paternalistic, or perhaps he kept it ironically to signify that he did in fact drink that evening.

In the rest of the scrapbook, Schmitt includes photos documenting his family and friends in the small Indiana town of Greencastle, his time in high school, his arrival at college, his dating life and eventual committed relationship with a woman, then road trip vacations to the western states. The impression given is that of the proverbial “all-American young man” (he even saved his high school varsity letter in the pocket of the scrapbook’s back cover). Having a bit of a wild time at a party in college—and breaking the law to do so—could fit in with the emerging narrative of American modernity and popular culture, as represented in movies, mass production, and the national news cycle.

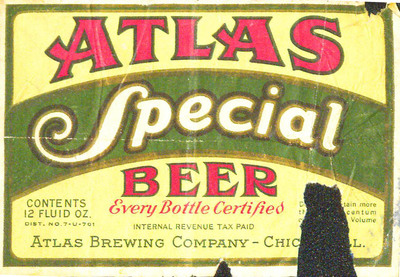

Atlas Beer Bottle from Lafayette, IN 1934

This beer bottle label was kept by 1935 alumnus Andrew K. Kolar because it was the first beer served to him after the repeal of prohibition in 1934. Although Purdue student regulations actually did not allow any “use of intoxicating liquors,” [3] which was in fact potential grounds for expulsion, Kolar—and presumably other students—celebrated the return of alcohol by going out for a beer. Since prohibition had been in place since 1920, this would have been a fairly momentous occasion for someone like Kolar, who would have grown up with that law in place. We might assume that this was his first beer ever, or perhaps it’s more likely that this was his first legal beer ever.

Reflecting on his memories of Purdue University fifty years after his graduation, Kolar describes in a letter the circumstances in which he was served this beer: “It was served me at Hook’s Drugstore in Lafayette and according to the law at the time, was only given if food was offered and bought at the same time. Hook, like the others, had sandwiches made up to be given with each beer and more than once, the sandwich was removed and the same sandwich given you when you ordered seconds. Some got pretty stale before they were either eaten or thrown away.” [4] This indicates that even though national prohibition had been overturned, there was still concern over the use of alcohol, especially by university students, and local ordinances frequently stipulated specific conditions under which alcohol could or could not be served. The letter also indicates that these stipulations were not particularly successful, if the intent was to curb the return of drinking-for-drinking's-sake.

Author Bio:

Dee McCormick is a third-year Ph.D. student in the rhetoric and composition program at Purdue University. They study rhetorics of health and medicine, in particular the history of research and argument surrounding drugs and alcohol in the United States. Their research interests also include queer studies, disability studies, and critical and rhetorical theory.

Citations

[1] Opal D. Stech Scrapbook, MSA 36, Purdue University Archives and Special Collections, Purdue University Libraries.

[2] Wilbur A. Schmitt Scrapbook, MSA 261, Purdue University Archives and Special Collections, Purdue University Libraries.

[3] Purdue Student Rules and Regulations, 1930-1931, Box 1, Folder 23, Purdue Rules and Regulations Governing Students Collection, Purdue University Archives and Special Collections, Purdue University Libraries.

[4] Andrew K. Kolar, Letter, 5 May 1930, Box 2, Folder 3, Purdue Customs and Traditions Collection, Purdue University Archives and Special Collections, Purdue University Libraries.